Traditional Method of Farm Succession Planning Broken…. Here is How to Fix it. Part III-Income Potential over Asset Value Arrives at Fairness

(Authors’ Note: This will be a several part series discussing why the current method of farm estate and succession planning is not working)

This is part 3 of a 5-part series regarding the authors’ view that farm estate planning in this country is broken and needs fixed, especially in light of “Farm Estate Armageddon” that will happen this decade when ¼ of all farmers retire and 2/3 of all farmers will be over the age of 65. Past articles can be viewed at www.farmlegacy.blogspot.com.

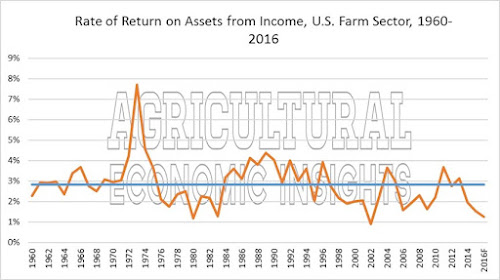

Why is farm estate planning so much different than other businesses? Well, to answer that question, we need to break down and compare farming, in general, to other businesses. Perhaps one of the most glaring differences between farming and other businesses is that farming is an “asset heavy-income light” profession. Two years ago, before we had a rebound in grain prices, I asked a lender what he saw as far as a rate of return on assets for farmers. The answer was 0.3 percent. Not 3 percent, but 1/3 of one percent. Not exactly a return that would make Wall Street envious. Studies from the USDA show that over the past 50 years, asset return rate for farms (excluding land appreciation) was around 3%. Take a look at the following:

Now let us look at some other professions. Consider an attorney, an accountant, appraiser, or similar white-collar profession. All three of these professions can easily generate $100,000 in income per year. From an investment standpoint (excluding the initial cost of schooling), the extent of assets needed is just about limited to a desk, phone, computer, and printer. In fact, a professional in any of these occupations could operate fine with $10,000 or less in hard asset investment, yielding a 10% return on assets.

Factor in the emotional attachment to the land (Note: I’ve never seen an attorney, accountant, etc, emotionally attached to their desk, phone, or computer), generational history of the farm, and other factors, succession planning for farming is tremendously different than that of non-farm businesses.

It is the volume of assets that a farm generally has that throws a wrench into succession planning. Historically, farmers have done the following as to an estate plan: a) split all assets among all the children equally or b) leave a little more assets/value to farming heirs, but still leave the non-farming heirs a very large slice of the pie. Estate plans most times end up with one of these two outcomes because farmers look at the value of what they are leaving each child, which is incorrect. Farmers should not look at the value of the assets they leave each child, but instead should look at the income generated by the asset. I view this as the fundamental problem with farm estate planning in this country.

Suppose we have three children, Peter, Paul, and Mary. Paul is the farming child. The farm estate value is 6 million dollars. Under “option “a”, stated in the last paragraph, the parents leave equal shares to each child, and they think that is “fair” because each child is receiving an equal amount. However, Peter and Mary want to sell their share. Paul wants to keep farming. Peter and Mary ultimately sell their shares to Paul, and each receive 2 million dollars which they put in an investment account earning 6%. Each year forward they earn $120,000. Paul continues to farm and goes into debt 4 million dollars AND gets to pay a lender 3-4%, or more, in interest each year. Who is the smart investor, the non-farm children earning a sizable income off of their inheritance or Paul who goes into debt 4 million dollars? From an asset return standpoint, Peter and Mary are the smarter investors.

Ok, but what about the appreciation of the land? After all, it has been about 40 years since we’ve seen land in this country decrease with any real significance. True, but you can’t eat your balance sheet and Paul only recognizes such gain from the appreciation if he sells. And, in reality, Paul does not really even inherit 2 million dollars of land. What does he inherit? He inherits the possibility to earn an income off the land that he inherits, i.e., his (USDA stated average) 3% return. Worse, because of the undoubtedly high price Paul must buy out his siblings for, his return won’t cash flow the purchase.

The theme still holds true under option “b” stated earlier. Even if Paul receives, let us say 50% of the farm assets, he still has to buy out his siblings to the tune of 3 million dollars, going into debt and pay a lender interest on that debt. On the flip side, the siblings get 3 million dollars, or 1.5 million each, and can invest and earn a lifetime of income off the investment. The takeaway is that parents think they are being “fair” when looking at asset values, but for those that do not want to sell, the asset value means nothing. Cash is king and it is the cash return that should be focused on.

Let us go a step further, and really talk about “fair” and in our example assume that Peter and Mary have never helped on the farm, contributed capital, or otherwise. How “fair” is it that the person (Paul) who has worked on the farm, contributed capital, and wants to keep the farm around for the next generation, gets to go into debt while people who have never helped can essentially receive a very large 401k? This situation generally only happens in farming. When looking at a lawyer, dentist, accountant, and a host of other professionals, you do not see a non-involved sibling getting a large value of the business. Why? Well, a) often times the real value of the business is the professional himself/herself, b) the son or daughter taking over the business could go start their own and most, if not all, of the book of business goes with them, and c) there is a low liquidity to the business. Do you think many professionals or other business owners “reward” non-participating children with a hefty chunk of the business? The answer is generally no, but this tends to be a trend which still repeatedly occurs in the farming industry.

The main reason current farm estate plans (or lack thereof) are wrong is that it is the value, and not the income generation of the assets that are looked at, and not enough value is given as to the efforts of the farming child(ren). It is nearly impossible to reach “fair” without a change of view on these two issues.

Do we need to even mention that with the high price of land, machinery, etc., unless a farming child receives a certain level of the estate (like, a very large majority of the assets) it is impossible for that child to continue farming? Sadly, the more that land and equipment increases in price, the less likely the continuation of farms occurs due to the simple fact that it is impossible to buy out the non-farming heirs.

So, there you have it. If we are going to fix how farm estate planning is done in this country, we need farmers to focus on the income, not the asset value, of what they leave to their heirs and give more credit to the children that have participated on the farm. If this were to happen, it would ensure the continuation of many, many more farms. In the next article, we will begin discussing various ways to achieve these changes.

John J. Schwarz, II, is a lifelong farmer and has been an agricultural law attorney for 17 years and is passionate in helping farm families establish succession plans. Natalie J. Boocher is a farm elder law and Medicaid planning attorney helping farmers protect their farms from the nursing homes and Medicaid.

Both can be reached at 574-643-9999 and www.thefarmlawyer.com.

Go to www.farmlegacy.blogspot.com for past articles.

These articles are for general informational purposes only and do not constitute an attorney-client relationship for specific legal advice.

Comments

Post a Comment